if MMA as a sport had been governed by rules analogous to the Muhammad Ali Boxing Reform Act, how might Cris Cyborg’s career have been different?

What protections or leverage might she have had? And how might perceptions of her “world champion” status versus UFC’s control of belts, rankings, and rematches have shifted under a more regulated, pro-fighter framework?

A quick primer: the Muhammad Ali Boxing Reform Act

Before diving into MMA, it helps to understand what the Ali Act (as passed in 2000) actually does in boxing, and its core objectives and mechanisms. Wikipedia+2Congress.gov+2

Key features and reforms of the Ali Act include:

-

-

Anti-coercion / promoter rights limitations

The Act prohibits a boxing promoter (or “boxing service provider”) from requiring a boxer, as a condition of participating in a fight, to grant the promoter promotional rights to future fights. Congress.gov+1

In other words, the promoter can’t lock a boxer into a long-term exclusive promotional contract just to fight, coercively binding her future. -

Transparency and disclosure obligations

Promoters must disclose their fees, the amount of compensation they receive, and other financial terms to the commission, and must provide full terms of the contract, and explain deductions, etc. Penn State Sites+1

Sanctioning bodies (i.e. organizations that award belts or authorize title fights) must make public their ranking criteria, bylaws, fee schedules, appeals procedures, etc. Congress.gov+2Penn State Sites+2

-

-

Separation of promoter and manager roles

The Act forbids a promoter from also being a manager (or having management interest) in the boxer, and forbids a manager from having promotional interests. This “firewall” is intended to protect the fighter from conflicts of interest. Penn State Sites+1 -

Private right of action / enforcement remedies

A boxer who suffers economic injury from a violation of the Act may sue in federal or state court to recover damages, costs, and fees. Penn State Sites+2NSUWorks+2 -

Regulatory oversight & commission support

The Act supports state boxing commissions in oversight, with disclosure to the FTC, public transparency, and oversight to discourage exploitative practices. Penn State Sites+1

In sum, the Ali Act is an effort to rebalance the power disparities between fighters and powerful promoters/sanctioning bodies, impose transparency, reduce coercive long-term tie-ins, and allow fighters legal recourse when abused.

While criticisms exist (some argue enforcement is weak, or that the Act has loopholes) NSUWorks+1, it nonetheless constitutes a federal backstop in boxing that curtails some extreme promoter practices.

In fact, there have been legislative proposals to extend Ali Act–style regulation to MMA, though none have become law in the U.S. Wikipedia+1

The structural difference: promoter control and belt ownership in MMA

In boxing, promoters and sanctioning bodies are (in theory) distinct from the fighters: promoters arrange fights, sanctioning bodies rate and authorize title fights, but no single promoter “owns” all the belts or all the rankings. Fighters may work with different promoters; sanctioning bodies are external entities. The Ali Act tries to enforce integrity in those relationships.

In MMA, by contrast, most of the top organizations (UFC, Bellator, PFL, etc.) operate as promoter + league + ranking + belt authority, in many respects. The promotion itself (e.g. UFC) owns the championship belts, controls the rankings, controls matchmaking, and often has exclusive contracts with fighters. That means the promoter is gatekeeper to not only whether you fight but whether you get a title shot. Because of this, a fighter leaving (or being unable to come to terms) with the promoter often loses control of their “champion legacy” in fans’ eyes: they cannot take the same belt with them, or force the promoter to allow a rematch. The promotional monopoly over the belt is a structural issue.

Let’s apply the Ali Act lens to Cris Cyborg’s situation to see how things might have been different.

Cris Cyborg’s career — points of tension and leverage

Let’s briefly outline the relevant portions of Cris Cyborg’s MMA trajectory to highlight how Ali Act–style protections might have helped:

-

Cris Cyborg (Cristiane Justino) built a nearly 13-year undefeated streak in MMA across multiple organizations (Strikeforce, Invicta FC, UFC, Bellator, PFL), often dominating her division.

-

She won major titles, e.g. Strikeforce Women’s Featherweight, Invicta, UFC Women’s Featherweight, Bellator Women’s Featherweight, PFL.

-

In UFC, she lost her featherweight title to Amanda Nunes at UFC 232 (December 2018).

-

After that, negotiations for a rematch were contentious. The UFC claimed it offered a rematch and that Cyborg turned it down; Cyborg responded that no rematch would be granted if she did not re-sign to a new (below-market) deal. MMA Fighting

-

She instead took a fight against Felicia Spencer (UFC 240) under her existing contract, regained a win, and publicly called for a rematch with Nunes. Nunes responded on Twitter minutes later, saying she was “ready.” ESPN.com

-

But Nunes largely declined or delayed a rematch. At one point (January 2019) she signaled she might make Cyborg wait two years for a rematch. MMA Mania

-

Over time, Cyborg left the UFC (as a free agent) and signed with Bellator. Meanwhile, Nunes did not defend the UFC women’s featherweight belt for extended periods. Because the UFC belt is seen as top-tier, many fans stopped regarding Cyborg as “world champion” (despite her dominance outside the UFC).

-

Even today, many casual fans regard the UFC belt holder as the “real champion,” in part because the promotion itself controls that legitimacy.

Thus, we see multiple pressure points: inability to secure a rematch (especially after having lost by knockout), contractual rigidity, promotional gatekeeping, and branding control by UFC over the notion of “champion.”

Below, I’ll run through specific ways an Ali Act–type regime could have benefited Cyborg in her negotiation, legacy, and visibility.

How an Ali Act–style regime could have helped Cris Cyborg

Here’s how various provisions or principles drawn from the Ali Act framework might have materially improved Cyborg’s position:

1. Preventing coercive long-term promotional lock-ins

One of the biggest leverage issues for top fighters is that promoters often require them to sign multi-year exclusive contracts or give future promotional rights as a condition to fight. Under the Ali Act, that coercive tie-in would be restricted. In MMA, if a fighter were prevented from negotiating with other promotions because of a long-term “deal or else” requirement, that would be curtailed.

For Cyborg, this could mean:

-

She would have more freedom to sign short-term or one-off contracts without fear the promoter would “hold her hostage” in negotiations.

-

If the UFC tried to condition a rematch on her signing a new below-market extension, she could more credibly refuse, without losing the legal right to demand the rematch or access.

-

She would avoid being penalized legally (or contractually) for declining an inferior deal, since the promoter’s coercion would be constrained.

2. Transparency in contractual and financial disclosures

Under Ali Act–style rules, Cyborg would have had the right to full disclosure of how much the promoter (UFC) earns from her fight(s), the breakdown of fees, deductions, and the promoter’s share of revenues. This transparency gives the fighter insight into their real market value, which strengthens negotiation.

In her case:

-

She could challenge claims like “we can’t afford to pay you more” by referencing disclosed promoter margins.

-

She could spot hidden fees or exorbitant deductions that weaken her purse.

-

In disputes over rematch terms, she could demand clarity on how much the promoter is making on the rematch and insist on fair splits.

-

If the promoter withheld or misrepresented revenue sharing, she could bring legal claims (e.g. under the private right of action).

3. A legal remedy (private right of action) for breached protections

If the promoter violated the regime (e.g. forced her into a bad deal, refused rematches unfairly, withheld disclosures, or had conflict-of-interest issues), Cyborg would have recourse to sue for economic damages. That adds real teeth to the rules.

For example:

-

If UFC refused a rematch on pretextual grounds, after previously promising one, she might sue for lost earnings or reputation damage.

-

If the promoter withheld disclosure of contract revenue or misrepresented their cut, she could enforce via court.

-

This threat of legal exposure would give Cyborg leverage in negotiations that is stronger than mere bargaining.

4. Protection from conflicts of interest (promoter/manager separation)

In MMA, sometimes the promoter, matchmakers, or executives may exert influence over a fighter’s management or career decisions. Under an Ali Act–style firewall, a promoter could not also manage a fighter or have undisclosed management ties. That safeguards fighters from being steered into deals favorable to the promoter rather than to the fighter.

In Cyborg’s case:

-

If UFC or its leadership tried to influence her management (e.g. by pressuring her to hire or fire certain agents), she would have legal protection.

-

Her management would be freer and more independent in representing her best interests, rather than being aligned with promoter interests.

-

Her side would be less vulnerable to conflicts where promoter decisions hurt her negotiation.

5. Mandated sanctioning body / independent ranking oversight

One of the structural problems in MMA is that the promotion itself often owns the championship belt and runs the ranking — so a fighter outside the promotion loses ranking visibility or ability to demand rematches. Under an Ali Act–style system, independent sanctioning bodies (or neutral ranking authorities) might be mandated, or the promotion would be required to recognize external sanctioning or ranking systems.

Thus:

-

Even if Cyborg left UFC, the external sanctioning body could rank her as number 1 contender. If the champion is there, the sanctioning body could mandate a rematch or enforce obligations on the promoter to allow the match.

-

The belt would not be “owned” exclusively by the promotion; the sanctioning body might retain oversight, so that promotional defections don’t void the belt’s legitimacy.

-

Cyborg’s legacy as “world champion” would be preserved more easily when she moves between organizations, because the belt’s authority does not vanish with the promoter.

In practical terms: after her UFC loss to Nunes, under such a regime, she might have been automatically ranked #1 contender in the sanctioning body’s system, forcing the champion (or UFC) to grant a rematch or risk being stripped.

6. Forcing rematch/matching obligations under sanctioning oversight

Many title-fight sanctioning bodies require champions to grant rematches or defend against mandatory challengers. Under an Ali Act–style overlay, a neutral body might require UFC (or any promoter) to grant rematches under fair terms or face stripping or sanctions.

Applied to Cyborg:

-

After losing to Nunes, the sanctioning body might have designated Cyborg the mandatory challenger and required the champion (Nunes) to defend within a certain time frame or lose the belt.

-

UFC would have less room to delay or block the rematch, or condition it on signing a bad deal.

-

The promoter could not simply “ignore” Cyborg in favor of other matchups or safer opponents.

7. Public accountability and legitimacy

With disclosure, sanctioning oversight, and third-party transparency, promotional decisions (who gets a title shot, who is bypassed) would be more visible and accountable. Fan perception could shift: if Cyborg continues to dominate in other organizations, the sanctioning body rankings, rematch mandates, and the public record would highlight how UFC is suppressing her, bolstering her legitimacy in public eyes.

In her situation:

-

Fans and media would more readily see that UFC’s ignoring of her is a breach of a fair system, not simply her failing.

-

Her status as a rightful champion or contender in the sanctioning body could remain front and center even outside the UFC.

-

She could leverage public pressure backed by formal regulatory mandates, not just media narratives.

Specific hypothetical “win paths” for Cyborg under Ali Act–style rules

Let me walk through a hypothetical scenario of how Cyborg’s UFC-era rematch and legacy might have evolved under Ali Act–style regulation:

-

Loss to Nunes at UFC 232 (December 2018)

-

Under the sanctioning body’s rules, Cyborg is designated the mandatory challenger or at least conferred immediate ranking status #1 (based on her dominance).

-

UFC (as promoter) is obligated to contract a rematch or lose sanctioning rights. They can’t simply refuse or bury the fight.

-

-

Negotiation of rematch

-

Cyborg declines the promoter’s attempt to force a long-term, low-value extension as prerequisite to rematch — that coercion would be illegal under anti-coercion provisions.

-

Cyborg demands full revenue disclosure and pushes for fair split. UFC provides promoter-side revenues and allocations, and shows those to commission or sanctioning body.

-

If UFC tries to delay or propose weak matchups elsewhere to dodge Cyborg, she can bring a legal or regulatory complaint to the commission or through her private right of action.

-

-

If UFC still delays

-

The sanctioning body may strip the champion of the belt or forbid defense against lesser opponents until the rematch is honored within a time window.

-

The promoter might have to pay penalties or sanctions to the commission.

-

Cyborg could push to take her “title shot” elsewhere under sanctioning umbrella, or challenge any competing titles.

-

-

If Cyborg leaves the promoter

-

Her status and ranking do not vanish. The sanctioning body keeps her as #1 contender. Any champion elsewhere (including UFC) must recognize her.

-

If she fights for Bellator or PFL under sanctioning oversight, those fights might count toward sanctioning body title paths.

-

Her legacy and “world champion” label do not depend exclusively on UFC’s branding and control.

-

-

Public and legal pressure

-

With disclosures and oversight, fans, media and regulators could scrutinize UFC’s refusal to match her, supporting Cyborg’s public narrative.

-

Cyborg might sue for economic damages (lost pay, sponsorships) if UFC’s behavior violates the regulatory framework.

-

In such a world, Cyborg might have been able to force the rematch (and perhaps win back the belt), or at least preserve a clearer “undisputed champion” narrative when she later shifted promotions.

Putting specific facts in the mix: Nunes delays & weight class issues

To ground this in what actually happened, let’s pull in some of the public record:

-

After her win over Cyborg, Nunes publicly signaled that Cyborg should wait two years for a rematch. MMA Mania

-

In 2019, Cyborg called out Nunes after her win over Spencer; Nunes quickly responded on Twitter saying she was “ready” for the rematch. ESPN.com

-

However, in media and interviews, the UFC claimed it had offered a rematch and that Cyborg declined. Cyborg countered that such a rematch would not be digitally possible unless she signed a new deal. MMA Fighting

-

Importantly, Nunes did not immediately defend the featherweight belt (145 lb) for a time; instead she moved back to bantamweight (135 lb) and defended there. That delay and shift undercut Cyborg’s contention that she was the rightful contender.

-

Because UFC holds the belt and is viewed as the ultimate platform, many fans viewed the UFC featherweight belt as the only valid “world championship” — once Cyborg was not in the promotion, her championship status faded from many casual views.

Under an Ali Act–style system, the sanctioning body might have forced Nunes to defend 145 lb (or lost the belt) rather than letting her linger in bantamweight defenses. Also, the delay and refusal to rematch would be seen as regulatory evasion, not pure promotional discretion.

Challenges and limits of applying the Ali Act to MMA

Of course, this is a theoretical exercise. There are practical challenges and limitations to trying to overlay Ali Act–style regulation onto MMA. Some of them:

-

Enforcement complexity in MMA’s multiple organizations

Boxing is relatively fragmented; there are many promoters, but the regulatory structure is narrower. In MMA, you have multiple large organizations (UFC, Bellator, PFL, ONE, Rizin, etc.) operating globally, with cross-jurisdictional complications (different countries, commissions). Enforcing a unified regulatory overlay across all would be difficult. -

Contractual sophistication and loopholes

Powerful promoters might find workarounds (e.g. non-promotional obligations, side deals, cross-licensing, non-disclosure barriers) to bypass protections. Regulatory agencies and courts would need strong authority, which might be resisted. -

Resistance from promoters and business models

Promotions like UFC benefit from their monopoly over belts, rankings, and talent exclusivity. They would likely strongly resist regulation that reduces their control or profits. Legal challenges or legislative pushback would be huge. -

Global jurisdiction, arbitration, international events

MMA events occur worldwide; jurisdiction and enforcement become tricky when fights happen overseas or under foreign commissions. The regulatory reach of U.S. law may be limited. -

Legacy contracts that predate regulation

Many fighters may already be locked into legacy deals; transitional complexity would be significant. Also, smaller promotions may lack scale to comply with heavy regulatory overhead. -

Ambiguities in structural design

Deciding how sanctioning bodies should be structured, how belts are shared or recognized, how to coordinate across promotions, how to ensure neutrality all present design challenges.

Thus, while the Ali Act offers useful guardrails, making them real in MMA would require careful legislative and regulatory design—and strong political will.

Conclusion: how Cyborg’s legacy might have looked different

In sum, if MMA had been regulated under a regime like the Muhammad Ali Boxing Reform Act, Cris Cyborg might have had far stronger leverage to demand a rematch with Amanda Nunes, maintain her “champion” status across promotions, and avoid coercive deals. She could have compelled the promoter to disclose financials, restricted oppressive contractual demands, invoked legal remedies if denied fair treatment, and benefitted from an independent sanctioning body that preserved her ranking and championship pedigree outside the confines of a single promotion.

In that alternate world, many of the narratives around her “fading” as a champion once she exited the UFC would be harder to sustain: she would remain in the sanctioning body hierarchy, forcing promotions to acknowledge her status (or face penalties). Fans would see more clearly whether the champion (inside UFC) was ducking her, rather than simply owning the narrative by default.

Latest from the blog

Friday, 9th Jan, 2026

Peter Murray leaves PFL MMA

LFA MMA leaves UFC FightPass joins VICE TV

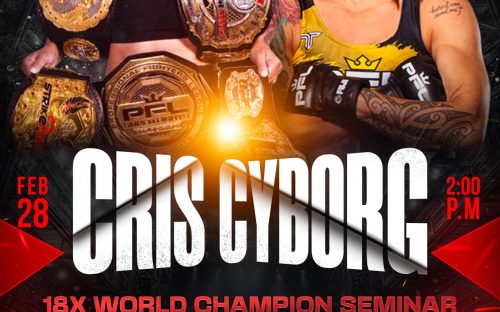

Cris Cyborg MMA Seminar Odessa Texas Feb. 28th

Amanda Serrano returns with Championship title defense

Kayla Harrison does not see value of Amanda Nunes training with Larissa Pacheco ahead of their fight